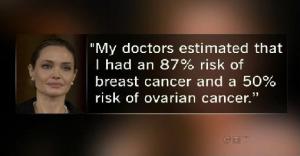

Like many women, Angelina Jolie’s recent public declaration in the New York Times of her preventative double mastectomy has had me thinking about my own health and whether I too may be at risk for breast or ovarian cancer. I’ve been fortunate enough to have been educated on the basics of women’s health issues since I was in my late teens. Every year since I was 17, I have gotten routine breast exams and pap smears and have also had frank conversations with my doctors about my health and my body. While living in China, it hasn’t been easy. Once I requested a breast exam at an exclusive foreign medical clinic and even there, the doctor just nonchalantly lifted up my shirt without any warning and started groping around while yacking on her cel phone with a friend and gave a nod when done. That aside, when I have had other medical issues, I have been fortunate enough to have worked with patient English speaking nurses and Chinese female friends who have accompanied me and translated for me on countless trips to local clinics when I have had medical issues. I have also been able to space out some doctor visits while in the US or New Zealand over the span of the last three years. During these visits, I try to squeeze in annual check-ups and I reserve the frank conversations about my current wellness and any preventative concerns for then.

I have always thought that my basic knowledge of female health issues and preventative measures were the norm for most women of my age. Lately I have been considering, however, that many women both in the US as well as in China may not have had the same exposure to basic women’s health education and preventative measures.

Here in China, I wasn’t entirely sure the level of exposure many women had when it came to their health basics as well as preventative measures. During various visits to public hospitals and clinics to take care of my own medical issues over the last three years, I surmised recently that many Chinese women probably have only limited exposure to preventative measures as well as routine health check-ups. I don’t think I have ever seen any information on any clinic walls nor anything in the form of informational leaflets that would provide women with information about self-breast exams, pap smears, or information and facts on breast, cervical or ovarian cancers. Then I started looking for information on the internet regarding breast cancer in China. What I learned after a quick search was that my assumption was mostly correct that many Chinese women have limited exposure and awareness of women’s health issues, especially breast cancer awareness. For example, an international study conducted in 2012 among a sampling of 400 women forty years and older in the city of Wuhan found that 75% of them had never had a mammogram because of a lack of priority; a lack of awareness; or because they were feeling okay (Chung, Liu & Wu, 2012). Though this study can’t speak for older or younger women across China, I am led to believe that preventative measures such as breast cancer screenings and breast exams, pap smears and frank conversations with doctors and nurses are uncommon. This led me to question why so many Chinese women likely lacked an awareness of these issues and why so many of them were also likely not talking about their bodies with their doctors or other health workers. So I set out to get some answers from some Chinese female friends as well as some of my female students. Of course they cannot completely represent the diverse experiences of the millions of women all across China in rural as well as urban places. However, their perspectives did help shed some light on some of my questions.

“It doesn’t affect us”

Women in China have not been kept completely in the dark about Angelina Jolie’s recent blog posting. A Chinese translation of the article was put on China’s microblog site Weibo (China’s version of Twitter) and thousands of people tapped into the article and commented on it (Guilford, 2013). Some of my female students had either heard of or had even read the article and were quite excited about it. A glamorous Hollywood actress with an equally, handsome and striking Hollywood husband will have no trouble garnering attention in China. My students exclaim, “Oh she’s so beautiful! I loved her in Mr. and Mrs. Smith!” When I asked them what they thought of her actions they responded that she was so brave and such a wonderful mother who wants to be there for her children when they’re older. But when I then asked them how they personally felt affected by the issue of breast cancer, they seemed relatively nonchalant.

These young women I spoke with said that they had never had a breast exam or pap smear nor had ever had a conversation with their doctors about this. Some of the younger women’s mothers had had conversations with them about monitoring their health. One savvy mother had gotten some information from her own doctor and then had shared with her daughter what she had learned. Mostly, though, these younger women believed that breast cancer or checking for cervical cancer were non-issues and they felt that they were still too young to take an active interest or concern in these issues. A couple of them had mentioned that there was no history of breast cancer in their family and that breast cancer is also not a disease that widely affects Chinese women, so why should they be concerned?

In addition to the experiences of younger women, I was also curious to hear the experiences of older and middle aged women. One friend of mine in her late 40’s mentioned that she and her peers had largely learned about breast cancer prevention and how to administer self-exams through relatives or other friends who had directly been diagnosed with breast cancer themselves. While it saddens me that many of the diagnosed women had likely not had a conversation about prevention with their doctors until their diagnosis, it at least brings hope that they are sharing their experiences with other women. Opening up about how they found lumps in their breasts as well as sharing advice on how to feel for different kinds of lumps is critical information passed from one woman to another.

So how widely are Chinese women really affected by breast cancer? While it’s true that only 1 in forty women in China is diagnosed with breast cancer compared to 1 out of every eight women in the US, 50% of women diagnosed with breast cancer in China are under the age of 50 (compared to only 20% in the US). Sadly, the number of cases of breast cancer is increasing each year in China. Thanks in part to pollution, poor diet habits introduced from the West, and poor healthcare, the mortality rate from breast cancer has skyrocketed in the last 20 years. Between 1990 and 2005, the breast cancer mortality rate increased by 155% and data projects the rate to only keep increasing (Breast Cancer in China, n.d).

Going to the doctor only when you are sick

Another possible reason why women may not be having conversations with their doctors about preventative health measures is that routine medical check-ups and physicals seem to be relatively rare in China. Therefore, visiting the doctor to check that you’re in good health will likely not happen. Doctor visits at even public hospitals and clinics may be expensive and too costly for the average Chinese woman or man who has to pay out of pocket for such visits. Having spent time in a couple of these clinics myself when I have had my own temporary ailments, I can honestly say that it is no picnic spending a day in one of these places. Navigating through a hospital for even a brief visit to see one doctor can be a really convoluted process. To see just for a few minutes a fuke, or a doctor specializing in women’s health, can be a long waiting game and then when it is your time, you are hustled into a small office. There’s almost no privacy with other health workers coming in an out and more patients waiting right outside the door pushing to get in as soon as you have your clothes on.

It is no wonder then why many Chinese people will reserve these dreaded visits to the hospitals for only when they truly need to go- which is when they get sick? Additionally, doctors’ time is also precious thanks to overcrowded facilities. Most doctors probably don’t have time to dillydally and chat with a patient about her medical history, her family’s medical history, and the technicalities of how to do a breast exam. Did you know that in China, there are 710 patients per physician? That’s 80% more than in the US where there are 398 patients per physician (Breast Cancer in China, n.d).

Therefore, I ask, when can most Chinese women afford the time and money to have such frank conversations with their doctors?

Mother and child first

In China, the fuke are typically under the same umbrella as the maternity wing of the hospital or clinic. While sitting in the waiting room for a non-pregnancy related issue, women at different degrees of pregnancy and their husbands can be seen making their way past. The infant wing and pediatrics section are typically close by as well. New parents are seen bringing their little babes in for check-ups. For someone visiting a women’s doctor for a non-pregnancy related issue, it sometimes seems a little like all other women’s health issues come second to prenatal and maternity care.

When it comes to women’s health issues in China, pregnancy or the ability to become pregnant is paramount. In a very family-centric country where couples can only have one child, an entire family will rally behind its pregnant woman. The child being carried by the woman represents the family’s future. A pregnant woman will get the best care possible with regular check-ups at the hospital to ensure her health and that of the baby. Even poorer families will try their best to find the best possible doctors and medical facilities for the expectant mother. While on a recent visit to Guizhou, one of the poorest provinces in China, I visited a first rate gynecological and obstetrics hospital. The president of the hospital emphasized how strongly he and his hospital felt about providing the best possible healthcare for women, in particular, future mothers, so that their families could rest assured that their future heir would be in good hands. Even far into the countryside, I saw signs for this hospital promoting its service to poor rural families leading me to believe that prenatal and maternity care are of the utmost importance for Chinese families across all economic classes.

So other than when a woman is pregnant or sick, when might she get a physical exam or see a doctor? My students told me that it is common practice for engaged couples to have a physical exam before they are married to ensure that they are in tiptop health to get pregnant after marriage. Both man and woman may get physical exams to ensure there are no infertility issues before marriage. In fact I was shocked to find out that if either partner is seen as unfit for conceiving children, the engagement may be called off and the couple may be urged to break up by the parents of the healthy man or woman. I thought that such practices were probably uncommon in this day and age or at least in the wealthier, more Westernized, urban parts of China. My students assured me, however, that it is still a common practice all over. Furthermore, if a bride-to-be or groom-to-be is found to have a history of cancer in her or his family, her or his fiancé has every right to break up the relationship. “But if they really love each other,” as my students said, “maybe they will stay together and fight for being together.”

“We are not as free as in the West when it comes to marriage. Maybe someday it will change in China”. The words of my students echo in my head. I wonder now if fear of being jilted at the altar or left on the shelf is another reason why some non-married Chinese women may not have more conversations about their health and their family’s health history. Could such conversations lead to unwanted bad tidings? Is ignorance bliss?

Reaching out to each other

I still have so many questions about the awareness of women’s health issues here in China. I’m learning to remain open-minded and non-judgmental of the medical system here, traditional viewpoints as well as the ways women in different walks of life here are getting information about these issues. When it comes to some issues, particularly breast cancer, progress is being made on the front of breast cancer screenings. Since 2008, free breast cancer screenings have been provided to Chinese women in rural settings (Guilford, 2013). Additionally, in the last five years, mammogram screenings have also increased sharply in urban hotspots such as Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou (Breast Cancer in China, n.d). Also, although many healthcare facilities may not be armed with the resources to provide all women across China with information about monitoring their health and taking preventative measures, it’s hopeful that women themselves are reaching out to one another within China and outside of China (case in point being Angelina Jolie’s article going viral in China). Women worldwide can learn from this example. Perhaps the safest and best way to educate ourselves is indeed to reach out and have these conversations with our sisters, our mothers, our daughters, our friends, our colleagues, our students, and our neighbors.

What are your experiences with women’s health issues in China or your own country?

Please feel free to share your comments or email me with your thoughts at travelforcause@gmail.com.

Additional resources:

– Angelina Jolie’s original op-ed piece where she went public about her preventative double mastectomy. This article cannot be linked from China.

Jolie, A (2013, May 14). My Medical Choice. New York Times.

– A Chinese translation of Jolie’s op-ed piece. A Weibo account is necessary to logon and read it.

Chinese translation of “My Medical Choice”

– A great data visualization of breast cancer statistics in China compared with the United States.

Breast Cancer in China. (n.d). GE Data Visualization. from http://visualization.geblogs.com/visualization/breastcancer_china/

– Education materials about breast cancer self-exams in Chinese from Susan G. Komen.

http://ww5.komen.org/Content.aspx?id=19327353809

http://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/Content_Binaries/BSA-Chinese-simplified_FINAL.pdf

– A 2011 study a done on breast cancer awareness and practices in China.

Chung, S., Liu, Y. & Wu, T. (2012). Improving Breast Cancer Outcomes among Women in China: Practices, Knowledge, and Attitudes Related to Breast Cancer Screening. International Journal of Breast Cancer, 2012 (2012). http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijbc/2012/921607/

– A recent article citing information about Angelina Jolie’s editorial in China as well as come statistics on breast cancer in China.

Guilford, G. (2016, May 16). Angelina Jolie reminds China that it’s woefully unprepared to fight breast cancer. Yahoo Finance. http://finance.yahoo.com/news/angelina-jolie-reminds-china-woefully-164744595.html